13 Product-building Lessons from Palantir

A former executive from the company that produces the greatest product managers shares her secrets to strong engineering partnership.

Hi there, it’s Adam. I started this newsletter to provide a no-bullshit, guided approach to solving some of the hardest problems for people and companies. That includes Growth, Product, and company building. Subscribe and never miss an issue. If you’re a parent or parenting-curious I’ve got a Webby Award Honoree podcast on fatherhood and startups - check out Startup Dad.

Questions you’d like to see me answer? Ask them here.

Marina Miller spent nearly 12 years of her career building on the front lines with Palantir. At Palantir, she worked as an Echo: a hybrid of product manager, operator, and strategist embedded with customers in the field. She grew to the Head of Internal Data, Head of Cloud, VP of Product Ops and SVP of Product, Operations and Delivery before leaving for Etsy where she led Product for ML, AI, Data, DevX and Experimentation.

I met Marina about a year ago and was so impressed I’ve been bothering her to write a guest post for my newsletter ever since. I finally won!

In today’s article Marina shares some of her personal notes, stories and lessons from working shoulder-to-shoulder with different engineering partners at Palantir in a forward-deployed environment. She’s never shared these stories of high-stakes, high-stress and fast pace anywhere else and I learned a lot from her throughout this writing process. Like my last guest post with Dan Birdwhistell it’s rare to get such unique insights out of the head of a practitioner who did the work in the trenches.

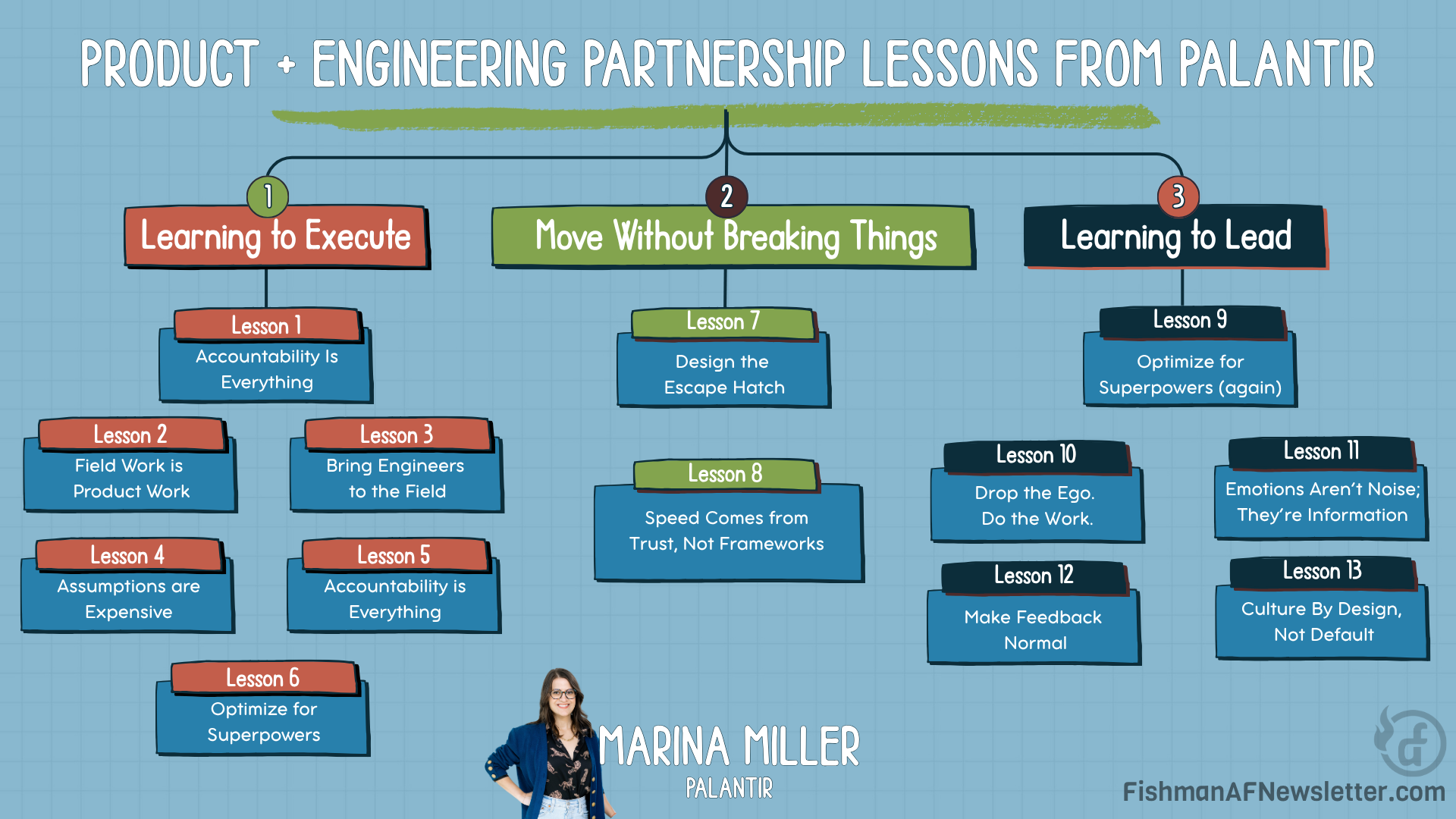

Read on to learn:

Why some of the most defining lessons of her career didn’t come from product frameworks or management books, but from her engineering partners.

How misalignment between execution and empathy breaks great ideas, and how shared accountability builds them back.

How speed depends on trust, not process, and how to move fast without losing people along the way.

How true partnership becomes culture, and how empathy and feedback scale an organization.

I especially appreciate some of Marina’s stories that didn’t make this newsletter, like her writing about being a working Mom while at Palantir.

Some names have been changed for privacy, but every story and lesson here is real.

The quality of your engineering partnership can make or break your ability to ship great products. Yet for all the talk about collaboration between product and engineering, there’s surprisingly little written about what those partnerships actually look like in practice - how they form, where they break, and what they teach you when you get them right.

At Palantir, I served as what we called an Echo. This is a hybrid of product manager, operator, and strategist embedded with customers in the field. Every Echo had a Delta, their engineering counterpart. Together, we were forward-deployed into government and commercial environments to build software side by side with the people who used it. We had badges, logins, and direct access to analysts, investigators, and decision-makers. It was product development at point blank range.

Some of the most defining lessons of my career didn’t come from product frameworks or management books, they came from my engineering partners. Each one shaped not just how I build products, but how I lead.

This essay shares three case studies of those partnerships and what they taught me:

James: How misalignment between execution and empathy breaks great ideas, and how shared accountability builds them back.

Krasi: How speed depends on trust, not process, and how to move fast without losing people along the way.

Brian: How true partnership becomes culture, and how empathy and feedback scale an organization.

Each partnership was different. One slow and methodical, one chaotic and high-stakes, one long-term and deeply trusted. Together they taught me that trust matters, how to forge it under pressure, and how to scale it into culture that outlasts any one relationship. They became the blueprint.

Learning to Execute with James

Where I learned that execution matters more than ideas.

James was the first real engineering partner I ever had at Palantir. It was 2012 and we were working on a federal law enforcement agency deployment together - what we called customer implementations. It was my first time building a real product for a customer. Following the forward-deployed model, we had badges, hands-on-keyboard accounts, and spent time with agents and analysts at the field offices. The intent was to truly understand their pain points before building features for Gotham, Palantir’s platform for investigative work and data analysis.

I was working with a financial crimes unit in NY where the entire division spent countless hours doing complex math on messy data for thousands of cases. James and I shadowed agents, analysts, and forensic accountants to observe their manual workflows when building cases. My product idea was an automatic calculator widget. A user would pull all of their relevant objects into Palantir Gotham, select them, select a few filters and hit “run.” In the background, the calculator would run all of the math formulas and produce the end result numbers that were previously calculated manually. When we launched it: crickets. No one used it. Here’s why and what I learned:

Lesson #1: Accountability is Everything

Work with your engineering partners to set realistic, specific deadlines, agree on priorities, and hold the line together on execution. Shared clarity on scope and timing prevents slippage and builds mutual trust. This was where I first learned that trust in product-engineering partnerships isn’t assumed - it’s earned through accountability.

When I proposed the calculator widget, I had full buy-in from the entire division - including the division head - but it still took weeks to ship the MVP. James was talented but moved slowly and I hadn’t pushed hard enough to define what the actual MVP was or when it needed to land. That lack of specificity eroded momentum and credibility. I learned that product and engineering have to align early on what’s realistic, write it down, and hold each other to it. Otherwise, “slow” becomes the default.

Lesson #2: Field Work is Product Work

Spend time embedded with customers to see how they actually work. What users say they need and what they truly need often diverge; direct observation exposes the real problems worth solving.

At the start, James and I thought we understood our users perfectly. We’d heard endless complaints from agents and forensic accountants about how tedious their math calculations were, so we built a helper to automate it. But we hadn’t realized that seeing the math was part of how they verified cases. By hiding those calculations behind automation, we broke their trust. If we’d spent more time watching their real process before building, we would’ve recognized that visibility was as critical as speed.

Lesson #3: Bring Engineers to the Field

Instead of filtering insights through specs or documentation, bring engineers to see users firsthand. When they experience the workflow themselves, they design smarter, more empathetic solutions.

Secondhand understanding is almost always incomplete. When engineers only read tickets or summaries, they miss the context that shapes a user’s real-world decisions. The best breakthroughs happened when James and I were both shoulder-to-shoulder with the agents, watching how they navigated Gotham. Those shared observations gave James the intuition to build tools that fit their environment instead of fighting it.

Lesson #4: Assumptions are Expensive

Validate your understanding before you build. Use quick prototypes to confirm that users’ mental models match yours. Catching misalignments early saves months of wasted development.

When we finally launched our “helper,” it technically worked. The math ran flawlessly in the background. But the forensic accountants immediately lost confidence when they couldn’t see how the calculations were done. Their entire verification process depended on visibility. If we’d shared a mock or walked through an early demo, we would’ve caught that assumption before building. The result was a perfect storm: a fragile UI, users who no longer trusted the product, and analysts unable to do their jobs.

Lesson #5: Depth before Breadth

Focus on the single user type whose success matters most. Broad consensus upfront often dilutes the outcome; depth for one audience creates a strong foundation others can adopt later.

Our team tried to build something that pleased everyone - agents, analysts, and forensic accountants - at the same time. In doing so, we served no one well. The widget worked for general math but not for the specialized needs of those who relied on traceable calculations. Had we focused on one primary user group, we could’ve built depth before breadth and earned organic adoption instead of forced consensus.

Lesson #6: Optimize for Superpowers

James and I continued working together on and off throughout my time at Palantir. What I’d initially seen as a frustrating weakness - his deliberate, methodical pace - eventually revealed itself as a strength when matched to the right problems. Years later, when he was assigned to complex, high-stakes search challenges that required painstaking investigation and careful analysis, that same pace became invaluable. The calculator widget didn’t fail because James wasn’t talented. It failed because we’d put a careful investigator on a project that needed rapid iteration.

Staff teams so individual superpowers fit the setup and ensure those strengths target business-critical outcomes. The sweet spot lies where capability, environment, and company priorities overlap.

Learning to Move Without Breaking Things with Krasi

Where speed, trust, and survival all blurred together at 30,000 feet.

James taught me the foundations of execution and product-market fit. My next partnership would test them in a very different context: operating at breakneck speed across messy, interdependent systems.

Lesson #7: Design the Escape Hatch

When doing foot-in-the-door custom projects for near-term revenue, keep scalability in mind. At the very least maintain excellent documentation and small, reversible pull requests. Otherwise you’ll end up maintaining unsustainable one-offs that stall progress toward a real product business.

When I worked with Krasi, it was my first time leading an entire portfolio with an engineering partner. Palantir had grown through a strategy of signing contracts with anyone who could pay and delivering massive amounts of custom work to make the product “sticky.” It worked. Our Gotham deployments were now mission-critical across government agencies, but the result was fragile. Each instance had evolved into a unique, highly customized system that the customer’s limited budget couldn’t sustain.

My job was to evaluate which deployments warranted continued investment, quantify the true cost of each relationship, plan graceful exits for those that didn’t, and preserve trust with our partners. Krasi and I were like a team of doctors: diagnose the code, the business relationship, and the operational health; decide what was worth saving; prescribe a sustainable treatment plan. I’d evaluate how each deployment was being used, the cost to support it, and the political stakes of exiting or scaling back. Krasi would dig into the technical implementation details to identify the exact work required to reach a stable, maintainable state. Then I’d take the findings back to the customers. Multiple difficult conversations explaining the transition plan, why it was necessary, and how they could continue using what we’d built by funding third-party contractors to maintain it.

This approach let us preserve the relationships and the impact of Gotham while freeing Palantir from the trap of endless custom maintenance. It also showed me the bigger risk: if you don’t build with scale in mind (or a clear path back to it) you stop being a software company and become a consultancy.

Lesson #8: Speed Comes from Trust, Not Frameworks

Working with James taught me that trust matters and how to build it through accountability. With Krasi, I learned how trust operates under entirely different conditions - at extreme speed with no time for frameworks or governance. Instead, build a rhythm grounded in:

Assuming positive intent. No time for defensiveness or second-guessing motives.

Asking clarifying questions without ego. No such thing as a stupid question when moving fast.

Focusing solely on the shared problem. Forget who gets credit, just make it happen

We were moving at hyperspeed. Flying constantly from Salt Lake City to Louisville, living out of suitcases, and waking up unsure what city we were in. Government shutdowns halted work without warning. Regulatory changes forced mid-project pivots. Technical solutions that looked elegant in theory collapsed under real-world constraints.

Through all of it, what made the partnership work was complete interdependence. Neither of us could succeed without the other executing flawlessly. The stakes were enormous: politically sensitive work, limited budgets, and a brand reputation on the line. We developed a simple operating rule - if one of us needed something, the other made it happen. No friction, no bureaucracy, just trust and velocity.

Learning to Lead with Brian

Where partnership turned into leadership and leadership turned into culture.

Krasi taught me how trust and psychological safety can be forged fast under pressure. Brian would teach me something harder: how to scale those same principles into a culture that outlasts any one partnership. This is how you build high-trust teams that can deliver mission-critical software at scale.

Lesson #9: Optimize for Superpowers (Again)

Brian is the best engineering partner I’ve ever had. We first met when we were set to lead a portfolio of U.S. government deployments together - me leading execution, him leading engineering. We started strong, but he was soon pulled to work on a custom system for a major federal customer, and Krasi took over the portfolio work. Over the next seven years, Brian and I worked together on different projects, and he became my most trusted engineering partner. I would work with him again in any capacity, any time.

After four years in the forward-deployed world, I needed a change. Brian recruited me to help tackle organizational execution problems, first on an internal data-platform team and later leading the cloud team. What made him exceptional was how he approached partnership. When I questioned whether I could lead engineers credibly as a non-engineer, he helped me see that I didn’t need to pretend to be something I wasn’t. He used first-principles thinking to break down what “technical leadership” really meant: someone who could work backward from outcomes, understand why the work mattered, and translate abstract goals into concrete priorities that teams could execute and deliver on. Those were exactly my strengths and he made sure I leaned into them.

It reminded me of what I’d learned years earlier with James - that people do their best work when they’re placed in environments that amplify their natural strengths. Brian lived that principle intuitively. Instead of trying to make me more technical, he helped me double down on what I already did best and built the space around me to make that matter.

Focus on amplifying people’s existing strengths rather than trying to fix their weaknesses or make them into something they’re not.

Lesson #10: Drop the Ego and Do the Work

To build credibility with engineers, take ownership of your learning plan. Don’t wait for permission or an onboarding process. Figure out what you need to know, do the work, and be willing to be wrong in front of people who know more than you. No matter how senior or accomplished you are, every new problem, team, or domain demands the same curiosity and humility - the moment you start leading from a distance without doing the groundwork, you lose the trust of the people building the product. Worst of all, don’t fake it; that destroys credibility in a way that’s hard to recover from.

When I moved into the cloud organization, I knew almost nothing about cloud infrastructure. Brian told me, “Don’t worry about the domain. It’s your skill set that we need.” So I got to work. No one asked me to get an AWS certification. It was something I felt would help, so I just did it. I also started a new ritual we called “murderboards”: I’d stand at a whiteboard and explain our entire system architecture while engineers interrupted to tell me everything I got wrong. It was uncomfortable, humbling, and exactly what I needed to build credibility.

Lesson #11: Emotions Aren’t Noise, They’re Information

When someone reacts strongly in a professional setting, be the Brian. Don’t write it off as an overreaction or drama. Lead with empathy, stay curious, and look for what that emotion reveals about context, motivation, or unmet needs.

When I came back from my second parental leave, one of my reports was running the cloud team beautifully, and I didn’t want to take that away from her. I went to Brian because I loved working with him and wanted to find a new way for us to collaborate. His first idea was for me to work on our FedRAMP accreditation - a federal compliance program that allows software to operate in government environments. This was a massive initiative with more than a hundred people already involved. For some reason - hormones, insecurity, postpartum state, whatever - I just started crying.

“I can’t believe this is what you want me to work on. There’s not even space for me.”

Looking back, I was being pretty entitled, but Brian didn’t judge me for falling apart. He didn’t owe me anything, but he understood that I’d come to him because I trusted him to help me figure out the next right thing. He gave me grace and treated my reaction as feedback rather than frustration. A few days later, he came back with a new idea: for me to be Chief of Staff to him and our Chief Architect. My new boss, who was deeply invested in my growth, encouraged me to counter with a proposal to join as an equal peer leading the entire org alongside them, not in a supporting role. They agreed.

Lesson #12: Make Feedback Normal

Give specific, impact-focused feedback in the moment and model how to receive it constructively. When leaders can openly receive feedback without defensiveness, it creates permission for everyone else to do the same. {Editor note: I just talked about this on the Best Manager Ever podcast}

Earlier in our partnership, when I spiraled over a difficult direct report, Brian was empathetic first. He listened and let me vent, but then he gave me direct feedback that my spiral would torpedo my reputation if I didn’t get it under control. It was hard to hear and exactly what I needed. That balance of empathy and candor became the foundation of how we worked together and set the tone for the feedback culture we later built.

As senior leaders, we continued that dynamic. We could give and receive feedback easily, even mid-meeting. Once, he told me right in the middle of a call that it was obvious I wasn’t paying attention and explained the impact not just on him, but on how it undermined the rest of the team. I paused, thanked him, and changed it immediately. That moment set the tone.

We modeled a feedback culture that was both direct and caring. It signaled to our organization that feedback wasn’t personal, it was how we got better together. As other leaders saw that dynamic play out they began doing the same with their teams. It became one of the cultural cornerstones of how we operated.

Lesson #13: Culture by design, not default

James taught me that trust comes from accountability. Krasi showed how it enables speed. Brian taught me how to scale it into an organization’s fabric.

We started with three teams and thirty people and eventually scaled to 150 people across fifteen teams around the world. I operationalized all of it, including building out new roles like TPMs, which would never have succeeded without the partnership Brian and I had. At that scale the best partnerships involve explicitly defining what you stand for together. Actively discuss your cultural values and priorities, then work to create that environment - even when it means uncomfortable conversations or resistance from leadership.

Our org had some brilliant technical leaders who struggled to create safe environments. Meetings sometimes ended with people upset or even in tears. The result was that our “best-idea-wins” principle had stopped working. People were too afraid to say the wrong thing so we weren’t surfacing the best ideas at all. We started losing great people who either transferred to other orgs or quit outright.

To course-correct we ran what we called a rubber-duck exercise around our cultural values and priorities. Talking through them aloud, challenging assumptions, and rewriting them until they actually reflected the environment we wanted to create. Together, we re-built that culture from the inside out. It wasn’t easy, but it worked: people felt safe again to speak up, challenge ideas, and contribute. That’s when the org started performing at its best.

Closing Thoughts

Technology changes fast, but breakthroughs don’t come from code alone. They come from partnerships built on trust, curiosity, and shared ownership - and from leaders who can scale that into culture. The best products aren’t built by process or frameworks; they’re built by organizations that make partnership a way of operating.

Really insightful post! The lesson about bringing engineers to the field resonates strongly - secondhand documentation can never capture the nuance of actual user workflows. Marina's experience with the calculator widget is a perfect exmaple of why proximity to customers matters so much in product development.