WTF is Strategy?

What it takes to build a great company and product strategy - with lessons from Hubspot, Reforge, Facebook, Nextdoor, Patreon and Imperfect Foods

Hi there, it’s Adam. 🤗 Welcome to my (almost) weekly newsletter. I started this newsletter to provide a no-bullshit, guided approach to solving some of the hardest problems for people and companies. That includes Growth, Product, company building and parenting while working. Subscribe and never miss an issue. Questions? Ask them here.

What happened to January?!? If you’re anything like me you’ve finally shaken off the fog of the first few weeks of the year and recommitted to your 2023 plans. Some of you may still be deeply immersed in 2023 planning. I’m sorry.

In honor of there suddenly being only 11 months left in 2023 today’s newsletter is about prioritization. Really though, and you’ll soon see why, it’s about strategy.

Recently, someone asked me a question about priorities.

“How do you handle the situation where there are multiple, “number 1” priorities in the company; especially when they are often at odds with each other?

Who among us hasn’t ended up in this situation? I would love to meet the person who says they haven’t. I don’t believe they exist.

Most people know about how to construct a prioritization 2x2, aka the Eisenhower Matrix. You can plot tasks on an Urgent/Important scale and work on the “Do Now” tasks that are high in urgency and importance. In fact, this framework has become so common that all your favorite SaaS planning tools have templates for them.

But what about the situation where everything is important and urgent. Templates and matrices won’t save you.

When teams and priorities seem at odds with each other and everything is the number one priority then you have a strategy problem.

Ahh strategy; there’s that word again. The bane of the startup’s existence and something reserved only for management consultants and people wielding powerpoint decks. Right?

WRONG.

In this post I’ll cover:

What strategy is (and isn’t) and why it matters

How to craft a great strategy

Case studies from Patreon and Imperfect Foods on both Company and Product strategy

Additional resources to explore

Because I don’t have ALL the answers I also opened this up to some of my peers and colleagues; people I’d consider to be excellent at shaping strategy for technology companies. You’ll see commentary and stories from:

Bradford Coffey - former Chief Strategy Officer at Hubspot.

Elena Luneva - GM at Braintrust and former Head of Product at Nextdoor.

Behzod Sirjani - Program Partner & EIR at Reforge and former research leader at Slack and Facebook.

Brian Balfour - Founder and CEO of Reforge and Venture Partner at Long Journey Ventures.

I chose to approach this from two different lenses—company strategy and product strategy. I’ll move between these throughout this post.

What strategy is (and isn’t) and why it matters

There are a lot of strategy definitions and the ones I like the best are simple and memorable.

Bradford Coffey described it succinctly as:

“How a company can – consistently, over a long period of time – (1) create value for its customers, and (2) monetize that value.”

Elena Luneva called it:

“The way to achieve the company’s vision.”

For me strategy is your plan to win.

The two key words here are “plan” and “win.”

What that plan (and winning) looks like will vary depending on the scope of what you’re describing.

For example, at the company strategy level you’ll include elements such as:

Your ambition - defining what winning looks like for you and your customers and why it matters. I like to include both a vision statement and concrete, multi-year targets around number of customers, financials, etc.

Your product offering - you’ll go into this in more detail in product strategy of course but important to include the themes of your product that will help you achieve your ambition.

Your audience - who is your target customer now and who do you expect it will be over time? How big is this market?

Competitive advantages - why will customers choose you over alternatives and what is your value proposition?

Defensibility - what advantages will emerge and persist over time?

Reasons to believe - these are the major, company-wide initiatives that you’ll pursue in order to deliver on your ambition.

For startups where the market is moving fast and the customer base changes rapidly, the longest time horizon I focus on at the company level is three years. Longer than that and you’re fooling yourself. Too much shorter and you’re often just creating a roadmap of work to do.

But Adam, thinking about three years into the future is hard!

Yes, it absolutely is. As you’ll see throughout it also takes a depth of knowledge that you won’t get overnight. But one of the aspects of strategy is that it’s composed of bets (your major initiatives).

Sometimes these are wrong. As you execute your strategy you figure which of your bets look right or wrong and which ones you need to change. This is all a normal part of the process of building and learning.

If you’re a leader, it’s your job to build the best possible strategy you can with all of the possible inputs and context you can gather or develop. So let’s open up that Google Doc and get started. (I’m going to help you here in a bit, don’t worry).

Behzod Sirjani described building and iterating on strategy with an amazing metaphor: Wheel of Fortune.

“The most helpful metaphor for me lately is making decisions as a company or as an organization is sort of like trying to solve the puzzle in Wheel of Fortune. You're looking at some set of unknowns and you're ‘ready to guess.’

And a lot of the negotiation that happens between people on a team is at what point do we feel comfortable trying to solve the puzzle. Because every other letter is an experiment, a customer conversation, or some other input. Ideally that input increases your certainty and decreases the risk that you’re going in the right direction.”

The most important part of strategy

Before I get to the next section I want to highlight one of the most important aspects of strategy: explicitly laying out what you won’t do. An excellent strategy is very opinionated on areas you will not pursue within the timeline you are highlighting.

Bradford Coffey articulated this to me from his time at Hubspot:

“We called these ‘Omissions’ at HubSpot. ‘Here are good ideas that we are NOT doing.’ In many iterations of the strategy, it was actually the most important part.”

Let me give you a specific example.

At Patreon for many, many years we were crystal clear that our role in the Creator ecosystem was to help creators monetize their fanbase directly. If someone could go from never having heard of a creator (step 1), to being a fan of a creator (step 2), to becoming their paying patron (step 3) then we wanted to tackle the fan to patron step (2 to 3).

The first step in the journey, otherwise known as the “zero to fan” step, was something we would absolutely NOT support. Why? Because there were plenty of companies out there with amazing discovery algorithms giving away creator’s content for free and paying them fractions of a penny from advertising dollars. We subscribed to the 1,000 True Fans concept and wanted to build our company around that.

Supporting the zero to fan step would require a fundamentally different approach to the customer we sought, the products we built, the markets we focused on and our monetization model. By naming this distinction and saying we weren’t pursuing it in all of our strategies (company, product, growth, etc.) we eliminated a lot of wasted time and energy.

What Strategy Isn’t

Just like in an excellent strategy; I should give you my “omissions.”

Here is a (non-exhaustive) list of what strategy is not:

Strategy is not a detailed list of tactics.

Strategy is not rigid; it can be revisited if it’s not working.

Strategy is not a hiring plan; it informs that plan.

Strategy is not your OKRs; it helps you set them.

Strategy is not an exact timeline or roadmap of delivery.

Strategy is not vision; it is the building blocks to get you there.

Strategy is not complicated; it is easily communicated and understood.

Why does strategy matter?

Often when people hear the term strategy they think of a group of executives going on an “offsite” and doing disconnected, executive things. Maybe they’re practicing a bunch of trust falls and returning with the grand strategy chiseled into stone tablets. Or they think strategy is a big company luxury and is worthless without great execution.

While it’s true that sometimes executives do go off and do disconnected, executive things it is also true that great strategy development is inclusive of a broader set of team members—those with deep context on your customers, your market(s), and the industry.

The second misconception, that strategy is a big company luxury that doesn’t matter, is fundamentally flawed. It assumes that if you just run hard enough in a particular direction you’ll win the race. And while great execution matters a lot it is also true that you have to know what direction to run to reach the finish line. Otherwise everyone lines up at the starting line for a relay, the race starts, and people sprint in all different directions.

If you’re working as a product manager, for example, you might make dozens of small decisions every day. Great execution means you can make those decisions swiftly, but the speed and ease of that decision-making is enabled by a great, well-understood product strategy.

How to craft a great strategy

There’s no sugar coating it; this is hard. And even though I’m going to show you some examples of strategy later in this post, those are sample templates. They’re the outputs and they’re not a substitute for the messy process that companies and teams go through to arrive at the finished product. I think that’s what has been lacking in the conversation around strategy. Quite simply: how do you do it?

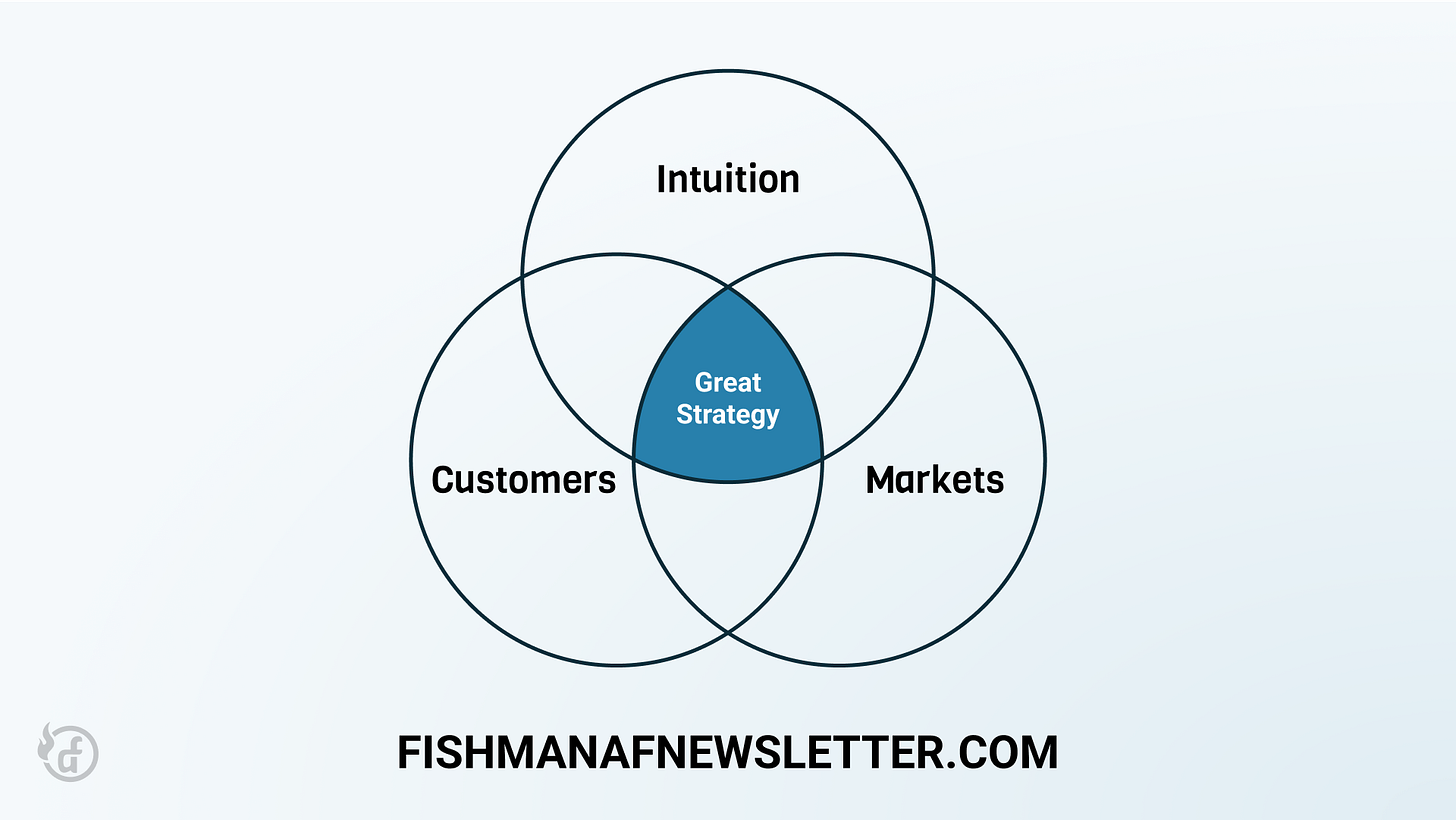

Great strategy is derived from three overlapping vectors: deeply understanding customers, understanding the markets they operate in, and developing intuition.

When I posed this opinion to some of my colleagues and peers I got really fantastic thoughts and feedback.

Brian Balfour on intuition as a vector:

“I think most intuition is developed by having lots of reps at the problem either directly or indirectly (through customer conversations and data). But we call it intuition because it's hard to describe all the little conversations, experiences, data points, etc. that are adding up in our head.”

Behzod Sirjani described strategy creation as one's ability to access a “pattern library” and know when to apply it:

“Intuition is just a very deep pattern library. I also think it’s about knowing how to apply those patterns. You have to know when these patterns do or don’t apply, and people’s intuition fails them when they blindly apply past patterns without asking ‘is this still relevant here’ or ‘why might this pattern not be a fit.’”

Bradford Coffey had a lot to say about what it takes to craft a fantastic strategy. In the early days of Hubspot they faced a pretty significant retention (churn) issue and needed to build a strategy to overcome it.

“The first major step was recognizing it as a problem and realizing if we wanted to hit any meaningful scale, we just couldn’t sustain it at those numbers. What we did over time was get much better at understanding our customer data and the voice of our customer. Specifically we merged our CRM data + financial data + our product usage data in an imperfect, but simple way that allowed us to segment our customers. We took this data and turned it into plays to get every part of the organization aligned against improving retention. We called it Mary, Mofu, Monetization.

Mary: Redistribute our sales reps up market to ‘Marketing Mary’ (>10 emp) persona, lean into working with agency partners, build features for this persona.

Mofu: Build out Marketing Automation, which led to us acquiring Performable and rebuilding most of the product from the ground up. Measuring customers' success based on utilization of these features. Developing services to get marketing automation set up.

Monetization: Change our pricing to align with contacts as the core source of ‘value’. Require paid onboarding [high-touch onboarding led to better retention]. Use sales comp structure to drive more annual-upfront deals.

To note: execution wasn’t perfect and we made many mistakes along the way. But we got enough general direction right to empower the team to iterate quickly towards good decisions. Without that execution the strategic direction wouldn't have mattered.”

“A good articulation of the strategy in my mind is:

Memorable. Use alliteration or some simple language.

Specific. Narrow the focus enough to empower folks to say ‘no.’

Measurable. Set specific goals to measure progress”

What Bradford is describing is deeply understanding your customers and your markets. They did this through merging and segmenting data across multiple, disparate systems and then once they had a clearer understanding of the important segments they changed their sales structure, their distribution channels, their product, their pricing, their onboarding and their metrics.

One of the often overlooked and messier aspects of crafting a great strategy is executive buy-in. Specifically, balancing an ambitious narrative with the time it will actually take to get there—even building the case to invest takes time.

Elena Luneva, underscored this point in Nextdoor’s Maps product strategy:

“For a company whose advantage is location, the company chose to orient around a news feed rather than a map, and I as the newly appointed Head of Maps and Strategic Partnerships was tasked with devising the strategy of how we change that.

I started with a small team of a designer and a user researcher so we could understand the market and customer needs, and prototype an inexpensive concept before making a decision to invest more people and time into the vision of turning Nextdoor into a map rather than a feed based app. It worked.

We defined and validated that there is a need for a map surface powered by small - neighbor insights, rather than big data (think Google), of local relevant information that was not served by other options completely. Today the map surface is its own tab and is getting progressively more useful with local events, and the ability to let others know you’re willing to help. The “help layer” was especially useful during Covid.

The hardest part between defining the vision and strategy was the length of execution and the need to carefully balance what I sold the executive team with the length of time it will take us to get there. There were also the table stakes features customers expected of a maps surface with the tiny team staffed to build it constantly competing with other new company investment ideas. What could have helped is multi-year incubation time baked into the portfolio strategy of bets that are expected to yield several years from their start time.”

The common theme across all of my conversations was that crafting a great strategy takes time and repetition. Yes, you can study Porter’s 5 Forces and take all the MBA courses out there, but that will just give you a framework to generate the output. It’s not a substitute for spending time with current and prospective customers, learning and internalizing market dynamics, and exercising the mental muscles that build intuition.

In the next few sections I’m going to share an abbreviated example of Patreon’s Company Strategy and Imperfect Foods’ Product Strategy. I’ll then elaborate on each piece and how we arrived at the insight and intuition that led to it.

Patreon Company Strategy

A market-defining, creator-first, SaaS membership platform

Here are some examples of these elements from our original company strategy at Patreon (circa 2018 or so). Since strategy is a living document that you revisit each year as new information emerges their strategy probably looks very different today. These are cliffs-notes designed to give you an idea of how to structure these sections and the thinking that went into them.

Ambition

Our mission is to fund the creative class.

In three years we want to establish Patreon as the world’s best creator-first membership platform. We define “Membership” as an offering that perfects the core of what creators need to deliver unique value to their patrons and thrive financially.

Our company goals were singularly focused on acquiring creators of a certain value and size. We had learned over time that once a creator reached a certain threshold on our platform their revenue retention was over 100% (net negative churn) and they had an outsized impact on bringing other creators onto Patreon simply by using the platform.

We knew from research that there were two primary reasons why someone became a patron: to support the creator OR to receive unique value and benefits from their membership. We knew “support” could happen anywhere, was something that made creators feel less successful (i.e. needy), and would always exist on our platform regardless of whether we optimized for it.

Reducing the barrier to delivering unique value was a much more ambitious and challenging undertaking. Creators were excited about generating revenue from a value exchange with their patrons, but it also couldn’t be too much work to do it or maintain it at a bigger scale.

Product Offering

We will offer a suite of products and services that comprise the “membership stack.” These products are designed to help our target creators turn their most passionate fans into paying patrons, deliver unique and ongoing value to those patrons, and nurture those relationships.

We will offer products across the spectrum of:

Building a membership

Turning fans into patrons

Delivering unique value to patrons

Getting paid

Owning and understanding your audience

We will specifically not:

Host audio or video content [Note: this has clearly changed as part of their evolution].

Help creators generate more fans vs. capture value from their existing audience (convert to patrons); this means not focusing on search and discovery.

Create a platform that allows developers to build services on top of Patreon’s data.

This underscored our goals and anti-goals or “omissions” as Bradford referred to them. If we were to be the world’s best Membership platform for creators—a category that we were creating—then we had to be the best product across the entire lifecycle of Membership. Creators needed our help converting fans to patrons, retaining those patrons and increasing their value over time. This surfaced during the course of several years through observation of creator behavior both on and off the platform.

Some examples:

Creating a membership with tiers, benefits, and pricing is really hard and creators tend to underprice their offerings.

At scale, continuing to maintain a robust membership program becomes very cumbersome. Creators became victims of their own success.

Creators valued reliability and predictability of payments (we were their paycheck)

Consistent value delivery was one of the keys to long-term patron retention.

Audience

We define our target creator as those who have built a sizable audience of highly engaged fans online, are serious about creating income from their work, and want to own and further the relationship with their biggest fans.

We defined these in a lot more detail that I’m not able to provide here for reasons that should be obvious to you :-). We learned through qualitative and quantitative observation that there was data we could capture that would tell us if a creator could be successful on our platform. That helped us narrow our target audience to this (simplified) version.

We believe that the number of creators who fit this criteria (i.e. the addressable market) is currently X and we assume the market will grow Y% per year. Based on the goals we outlined in our “Ambition” section we estimate this represents capturing Z% of the market.

We studied the market across key creator platforms, conducted consistent and longitudinal qualitative surveying, looked at the rise of copycat solutions from both big platforms and small, and observed the growth in the earnings of our biggest creators who launched on our platform. This gave us a sense of the size and expansion potential of the overall market for our offering.

Competitive Advantages

Why will creators specifically choose us over alternatives?

You own your audience. Our relationship is with you, not your fans and our products will support the nurturing of the relationship with your patrons.

Business model alignment. We have no revenue lines that are orthogonal to creator interests.

Neutral, independent platform.

We had several more competitive advantages that I won’t list here; also for reasons that should also be obvious. We heard #’s 1 and 3 loudly and consistently from creators. They hated “the algorithm” and we represented a great alternative. We weren’t beholden to advertisers and we were transparent in our communication and decision making. We had a lot of validation from a growing creator base that leaning into this was valuable.

Defensibility

Why will competitors have a hard time catching up to us over time?

There are two types of competitors: Big, tech platforms and smaller, vertical-specific platforms.

Defensibility against Big Tech

We will continue to have multi-category breadth. Most of the Big Tech platforms play in one or two specific verticals but most creators aspire to be multi-medium.

We will support advanced creative businesses. We will offer tools and services that are attractive for creators with larger audiences and more sophisticated businesses. In this way, Patreon will be positioned as the membership platform creators graduate to when they are ready for something more than the cookie cutter solutions by the tech giants.

Diversity and Breadth of benefits. Because we are singularly focused on Membership we will continue to provide the tools that enable creators to deliver a wide range of unique benefits and can leverage our vast membership data to make smart, timely recommendations for different creator types.

We are the most creator-first platform. Patreon only succeeds when creators succeed and thus we naturally prioritize creator success above all else.

Defensibility against Smaller, Vertical-Specific Competitors

Economies of Scale. The larger our base of creators and customers the more we can drive costs down for our creators.

SaaS Stickiness. Once you’ve invested time in our tooling, our automation, and our data it’ll be hard to go elsewhere.

Multi-category breadth. It is impossible to fulfill our mission without supporting creators across a variety of categories – and creators want that. Vertical-specific competitors won’t be able to reach the scale necessary to succeed in a single category.

We knew our advantages over both big and small tech from talking to creators about their experiences with those platforms and studying the landscape. For example, the big tech platforms are largely distribution mechanisms for content, monetized by advertising. And while creators crave distribution they also crave diversity of medium. Most aspire to be “multi-modal” which means making a podcast, recording it as a video, and running a merchandise business (for example). We would provide a place to monetize it all, without worrying about the algorithm. We also knew that the depth of turnkey benefits that a big platform would offer would largely be limited to experiences on that same platform.

Reasons to Believe (i.e. Major Initiatives)

In this area of the document we covered 5 major initiatives that would propel Patreon forward across multiple years. Each of these had their own strategy behind them.

International Expansion

Merchandise

Payments

Memberful (complete customization)

Pricing & Packaging

Each of these bets represented a significant opportunity to achieve our ambition.

For example, because we had studied creator markets closely we knew that 65-85% of the potential creator market (and therefore revenue) was outside of the U.S. and we knew that our customer base was very U.S. centric. To continue growing, and reach our goals, we needed to open up the platform to be much more friendly to non-U.S. creators. Thus International Expansion was a key initiative for the business over the next 3 years.

Merchandise was a “super benefit” that creators wanted to offer their fans. Over 85% of them rated Merch as a “must have” or “nice to have” product for running a membership business. Through observation and research we knew that some of the more ambitious ones were even attempting to do it on our platform albeit with a lot of incremental work. If we wanted to reduce the barriers to offering unique value then turnkey Merchandise creation and delivery was one of the primary ways to achieve it. At scale, it also opened up new revenue options incremental to our membership fees.

One aspect we struggled with at Patreon which is a common challenge for many companies is simplicity.

As Bradford Coffey says,

“The company strategy should be simple. The key is to get all the vectors aligned, and make it very clear to everyone.”

“One good litmus test: can you write your strategy easily on a white board? Would many leaders or employees write it the same way?”

“Many companies struggle with getting this piece right. They often suffer from either being overly detailed in their plays (e.g. 15 ‘priorities’) or overly generic (e.g. ‘deliver customer value’). So companies either have a strategy that’s too complicated and no one can remember — or it’s so broad that folks can justify any play they want to run. A good strategy is simple enough to remember, and specific enough to empower folks to say ‘no’.”

Now that you’ve seen the hard work of crafting a company strategy—the need to understand customers, markets and develop intuition—let’s look more closely at the work required to develop a great Product strategy.

Imperfect Foods Product Strategy from 2021

Delivering on our vision: It just shows up.

First, it’s important to understand the vision for the Imperfect Foods product experience. This is told from the perspective of a handful of customers. We wanted to craft a first-of-its kind, effortless product experience that saves the planet in the process.

Shout out to Patti Chan, a leader on my team who was instrumental in shaping this vision.

In approaching Imperfect Foods Product Strategy it’s also important to understand the macro environment the business was operating in around the time that this was created ~April 2021. The company had just finished a strong year of growth fueled by the “stay at home” orders of Covid. In 2019 we generated ~$150m in revenue and in 2020 we were close to $600m (4x YoY growth!).

We had over-invested and scaled operations (albeit somewhat shakily), marketing expenditure, and our product offering (food, not pixels). However, our shopping experience and warehouse technology were woefully behind customer expectations because that investment had not kept pace with the rapid growth of the business. The pandemic ushered in a wave of new shoppers almost overnight and the team couldn’t build fast enough to catch up.

We went from a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) box filled with ugly produce to a full-service, subscription grocer with hundreds of thousands of brand new customers. Those customers were comparing us to Instacart and Doordash with product and technology teams 50x our size. Our CEO and my fellow C-suite members wanted us to be all things to all people immediately (much like the question posed at the beginning of this newsletter) and in order to focus and prioritize I laid out our product strategy.

To summarize our company strategy:

Imperfect will be the most sustainable way to buy food, the most affordable way to buy “ugly” produce and deliver the freshest product in the fastest time.

In doing so we will create and expand a line of exclusive branded and private label products, ensure they are delivered reliably and on our customer’s terms, and engage customers in a delightful shopping experience that removes the chore of grocery shopping.

Because of our first core differentiator (sustainability) we will do all of this while balancing being the most sustainable way to buy food.

In supporting the company strategy the overarching goal of the Product strategy was to realize our vision:

Deliver an effortless, recurring shopping experience that is intuitive and delightful from your first visit.

I broke our strategy into three distinct pillars.

Nail the basics of an intuitive grocery delivery experience.

Increase flexibility and convenience across shopping and delivery.

Create a fully personalized shopping experience that delivers delight.

To further simplify, you could remember these as:

Nail the basics.

Increase flexibility.

Personalize the experience.

There’s nothing particularly earth-shattering about this strategy. My pal Casey talks about this dirty secret of product strategy in a post exploring his first year as a CPO. This strategy, much like the Patreon company strategy, was derived from a deep understanding of customers, the external market, and intuition.

You’ll notice I followed similar principals that Bradford laid out in the company strategy: simple and memorable.

The first pillar, nail the basics, was rooted in observation about customer expectations for a sustainable, online grocery store and the key problems our product failed to address:

Our signup experience was confusing and non-standard; product availability and what we sold wasn’t obvious because of a CSA-style delivery approach we had coalesced around since the company’s founding.

Our shopping cart and storefront were also non-standard and with a plan to expand to 1,000+ shoppable SKUs it would get worse.

Search and discovery were almost non-existent; showing related products or bundles was not possible.

Once we had nailed the basics of an online grocery store we needed to address the second pillar: increase flexibility.

From the product strategy:

Because customer expectations are never static (and always increasing) we can no longer rely on our mission alone as an excuse for a rigid experience. We must adapt because the market will not.

While we were the world’s most flexible CSA box we were simultaneously the most inflexible grocery store.

The key customer problems to solve here were:

Because we relied on “shopping windows” as a relic of our CSA roots customers had a lack of visibility into what we offered when shopping windows were closed

Delivery day and time was fixed, again a byproduct of the CSA model.

Shopping wasn’t oriented around customer needs—think recipes, not items.

After nailing the basics and increasing our flexibility the final pillar and key differentiator came in taking advantage of our data network effects to deliver a fully personalized and mostly automated grocery experience.

Here’s how I described this in our Product strategy:

Our last strategic hurdle in transforming the chore of grocery shopping into an experience that is unique and delightful. If we can save you time and money, bring you some joy in your day, and maintain our leadership position in sustainability we will maintain a long-lasting relationship with our customers.

We will establish and grow a robust repository of data around our customers’ preferences -- their likes/dislikes, their shopping habits, even their favorite recipes -- in order to deliver an experience that feels unique to them.

I then went on to outline some key problems to solve in this area:

Customers can’t signal their grocery preferences to us and we can’t infer them

Our experience is unaware of individual customer preferences

As our offering grows the store will become too large for customers to navigate successfully

Our merchants cannot successfully create carts with a growing catalog (would you believe that our merchandising team was uploading spreadsheets to generate recommended items in your cart every week?!?)

Because there was a never ending stream of ideas from the rest of the leadership team I also leaned heavily into the “omissions” or anti-goals as I called them.

Reaching parity with other services: we will invest in the features that matter most to our customers and make sense within the context of our business

Changing our subscription model; we could consider this in 12 months but not before then

Parity between the web experience and app experience is not an explicit requirement

Revamping or additional investment in our Fedex/3PL shipping product

On-demand delivery

What this strategy did was two-fold. First, it laid out a product experience that would first meet the expectations of our (now quite large) customer base. Second, it set us on a path for the post-COVID era by anticipating that those expectations would continue to rise when it was easier to return to the grocery store. I didn’t expect that 2022 and beyond would look much like 2021. And it turned out I was right!

Closing Thoughts

Building a great strategy is a hard but necessary step for any company to take. It can start very early, and tops-down with the founder/CEO, but eventually ends up requiring a broader set of team members who have deep understanding of customers and markets. There’s no avoiding this. Even brilliant strategists with omniscient-like intuition have likely developed that intuition from repetition with the problem. As Brian said, “it's hard to describe all the little conversations, experiences, data points, etc. that are adding up in our head.”

And this is why crafting a great strategy is so difficult and also why no one talks about what it takes. It’s messy, it takes time, and even then it’s not certain to work. My hope is this post has equipped you with enough information to get started on the hard work of building your own strategy.

A special “thank you” to Bradford, Elena, Brian and Behzod for taking time with me and lending their experience and expertise.

Here is some of my other favorite reading on this topic:

Lenny Rachitsky on Strategy (paywall) -

Ravi Mehta - Product Strategy Stack

https://www.ravi-mehta.com/product-strategy-stack/

Casey Winters on Wartime Strategy

https://caseyaccidental.com/fire-every-bullet/

For those with more time to invest

Reforge Product Strategy Program

https://www.reforge.com/programs/product-strategy

Good Strategy / Bad Strategy Book

https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/11721966

For fun, here’s the OpenAI response to the title of this post — factually accurate, but not nearly as fun:

Simply deciding what to do and what not to do

Loved how the article was simple to understand, yet quite detailed and complete.

I wrote one article that might be interesting to whoever liked this one: https://www.productleadership.io/p/your-company-strategy-is-sht